Bee aware, but not alarmed: here's what you need to know about honey bee stings

- Written by Ronelle Welton, University of Melbourne

Bees don’t attack unless they feel threatened.Shutterstock

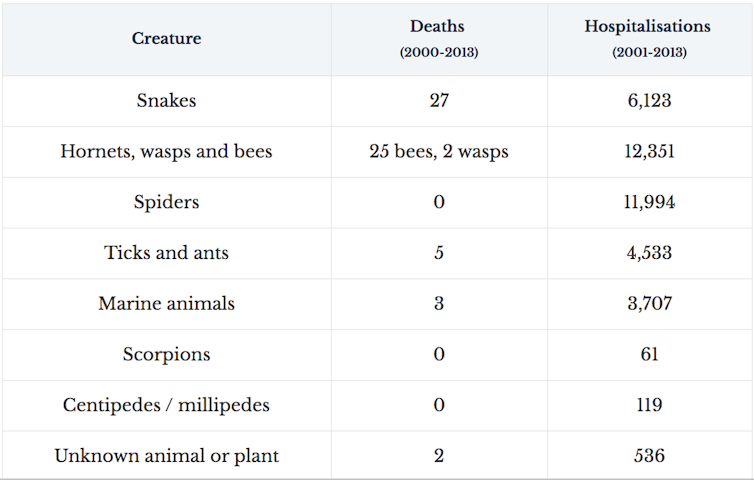

Bees don’t attack unless they feel threatened.ShutterstockA Victorian man died yesterday after being stung by several bees. While bee sting deaths are rare (bees claim around two Australian lives each year), bees cause more hospitalisations than any venomous creature.

Bee stings cause nearly the same number of deaths each year as snake bites.The University of Melbourne's Pursuit/Internal Medicine Journal

Bee stings cause nearly the same number of deaths each year as snake bites.The University of Melbourne's Pursuit/Internal Medicine JournalAround 60% of Australians have been stung by a honey bee; and with a population of more than 20 million, that’s a lot of us who have just experienced pain and some swelling.

So what happens when we’re stung by a bee, and what determines whether we’ll have a severe reaction?

Further reading: Ants, bees and wasps: the venomous Australians with a sting in their tails

How do bees sting?

Honey bees work as collective group that live as a hive. The group protects the queen, who produces new bees, with worker bees flying out to collect nectar or pollen to bring back to the hive.

Bees have a venom sac and a barbed stinger at the end of their abdomen. This apparatus is a defensive mechanism that is used if they feel under attack; to defend the hive from destruction. The barb from a bee sting pierces the skin to inject the venom, with the bee releasing pheromones that can incite other nearby bees to join the defensive attack.

Honey bees work as a collective.Shutterstock

Honey bees work as a collective.ShutterstockThe venom is a complex mixture of proteins and organic molecules, that when injected into our body can cause pain, local swelling, itching and irritation that may last for hours. The specific activity of some bee venom components have also been used to treat cancer.

Further reading: Curious Kids: Do bees ever accidentally sting other bees?

A single bee sting is almost always limited to these local effects. Some people, however, develop an allergy to some of these venom proteins. Anaphylaxis, a severe allergic reaction that is potentially life-threatening, is the most serious reaction our body’s immune system can launch to defend against the venom.

It is our body’s allergy to the bee venom, rather than the venom itself, that usually causes life-threatening issues and hospitalisation.

How do I know if I am allergic?

If you have not been stung by a bee before you are unlikely to be allergic to the venom. However, if you have been stung by a bee, there is the potential to develop an allergy. We do not know why some people become allergic and others don’t, but how often you are stung seems to play a role.

If you have experienced very large local reactions from a bee sting, or symptoms separate from the sting site (such as swelling, rashes and itchy skin elsewhere, dizziness or difficulty breathing) you may have an allergic sensitivity. Your doctor can assess you by taking a full history of reactions. Skin testing or blood allergy testing can help confirm or exclude potential allergy triggers.

An allergy specialist is key to assess people’s risk of severe allergic reactions (anaphylaxis).

There is an effective treatment for severe honey bee allergies, called immunotherapy. This involves the regular administration of venom extracts with doses gradually increased over a period of three to five years. This aims to desensitise the body’s immune system, essentially to “switch off” the allergic reaction to the venom.

Venom immunotherapy is very effective at preventing severe reactions and is available on the Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme, whereas other immunotherapy treatments in Australia cost an average of A$1,200 per year.

First aid for a bee sting

Bees usually leave their barbed sting in the skin and then die. Remove the sting as soon as possible (within 30 seconds) to limit the amount of venom injected. Use a hard surface such as the edge of a credit card, car key or fingernail to flick/scratch out the barb.

For a minor reaction such as pain and local swelling, a cold pack may help relieve these symptoms.

If a bee stings you around your neck, or you find it difficult to breathe, or experience any wheezing, dizziness or light-headedness, seek medical advice urgently.

Prevention

Despite being a species introduced by European settlers, the honey bee (Apis mellifera) plays an essential role within Australian agriculture. We need to appreciate their essential functions, and try to prevent stings.

Read more: Losing bees will sting more than just our taste for honey

If you see a bee let it be (sorry); don’t swat it or step on them. Our bees don’t attack unless they feel they need to defend their hive.

Do not attempt to locate a hive, call an expert.

For more information on allergies go to the ASCIA website. Local bee keeping groups are a good source of knowledge about local bee populations.

Ronelle Welton has previously received funding from the NH&MRC.

Kymble Spriggs is a specialist member of the Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology & Allergy (ASCIA); and a board member of the Insect Venom Hypersensitivity Working Group of the European Academy of Allergy & Clinical Immunology (EAACI) - both non-profit organisations for the promotion and dissemination of Allergy Research, Education and promotion of patient care.

Authors: Ronelle Welton, University of Melbourne