Don't let your pet accidentally get drunk this silly season (sorry Tiddles)

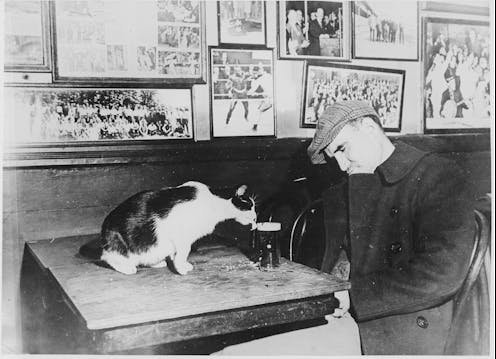

1947 - A patron of "Sammy's Bowery Follies," a downtown bar, sleeping at his table while the resident cat laps at his beer.Wikimedia Commons

1947 - A patron of "Sammy's Bowery Follies," a downtown bar, sleeping at his table while the resident cat laps at his beer.Wikimedia CommonsMost responsible pet owners know that animals and booze don’t mix, but with the Christmas season upon us, many Australians will be drinking a little more than usual.

While most pets aren’t generally interested in alcohol itself, rich treats like cream liqueurs, brandy-soaked puddings and eggnog might tempt their palate. Your pets can get tipsy without you noticing, so it’s worth knowing the risks (and symptoms) of alcohol poisoning.

For many domestic animals, alcohol is toxic. Ethanol poisoning can result in depression of the central nervous system. The animal becomes drowsy and uncoordinated, progressing to loss of consciousness, respiratory failure and potentially death.

Read more:Spare a thought for our furry friends this Christmas

Pup in the pub

There is relatively little research on acute alcohol poisoning in animals, although it’s possibly under-reported by owners who fear being judged, or aren’t aware of the source of their pet’s distress.

Unintentional alcohol poisoning is illustrated by a case study presented in the Australian Veterinary Journal. A 4-year-old male dachshund was taken to a veterinary hospital with symptoms including continuous whining, coupled with uncoordinated running and bumping into walls. Poisoning was suspected and the dog was given general treatment for an unknown poison, as he lapsed into unconsciousness.

The owners returned home and discovered their other dog, a 4-year-old female dachshund, suffering similar symptoms. During treatment, both dogs vomited a creamy yellow substance, which the owners later realised was their home-made Advocaat (alcoholic eggnog) that had been stored in a milk bottle and fed to the dogs by mistake.

Had it not been for the distinctive vomit, alcohol poisoning would not have been diagnosed. Luckily, both dogs recovered after intensive veterinary care.

Alcohol on its own is not likely to be attractive to our pets. However, as in the case of the drunk dachshunds, when coupled with other ingredients like egg yolks, sugar and cream, the concoction proved too tempting to resist.

It could happen schooner or later

Many mammals have a taste for sweet things and this can unwittingly lead them to drinking toxic solutions, such as syrupy, sweet antifreeze, resulting in ethylene glycol poisoning. This is one of the most common forms of poisoning in dogs and cats.

Dogs have been observed drinking highly chlorinated water from outdoor pools on a hot day. A 2005 study conducted at the University of New England showed that dogs prefer cool water (15°C) over water at warmer temperatures (25°C and 35°C).

While the most common result of human drinking is a hangover, our pets have more dangers to contend with. Even ingredients used in alcohol production may be toxic to them. For instance, the grapes in wine could cause acute kidney failure. Consuming hops, which are used to make beer, may result in malignant hyperthermia, vomiting and even death.

Pets may also ingest alcohol by accident, when present in medicinal syrups, rubbing alcohols and fermenting bread dough. Owners who leave food or drinks on countertops, expecting it to remain safe, may be surprised when their dog high-jumps and devours the raw dough (which continues to ferment in the stomach). Dogs are opportunistic eaters, sometimes considered scavengers. Their relentless pursuit of tasty things may result in them consuming dangerous substances.

Read more:By studying animal behaviour we gain an insight into our own

Cats have fairly narrow taste ranges, with most showing a strong preference for meaty flavours and without the ability to taste sweet flavours. However, they do enjoy fats and will gladly consume milk, ice-cream or a lonesome glass of Baileys. When encountered with an unpleasant taste, they stick their tongue out in a “tongue protrusion gape”.

Cats display distinct facial expressions to pleasant and unpleasant tastes. When enjoying a pleasant taste their eyes may be half shut. When encountering unpleasant tastes, they stick their tongue out more.Didgeman/Pixabay, CC BY

Cats display distinct facial expressions to pleasant and unpleasant tastes. When enjoying a pleasant taste their eyes may be half shut. When encountering unpleasant tastes, they stick their tongue out more.Didgeman/Pixabay, CC BYBut of course many people enjoy sharing experiences with their pets, including meals. For those who want to spread a bit of Christmas cheer among their furry friends, a whole range of non-alcholic pet drinks are available. (Most lean heavily on puns: Pawsecco, Dog Perignon and Pinot Meow, for example.)

Or, we could all stay healthily sober and stick to water!

Intentional alcohol consumption

Animals may intentionally imbibe alcohol, enjoying over-ripened and fermenting fruits. Butterflies have been known to enjoy a beer brew and beer traps are commonly used to catch snails. Sometimes, lack of a mate may drive fruit flies to consume food containing alcohol.

While few domesticated animals intentionally consume alcohol, and are almost certainly not doing so for its intoxicating effects, humans have been known to give their pets a sip of their favourite tipple or a saucer of beer. However, very few owners give alcohol to their pets intentionally, according to Emergency and Critical Care Veterinarian Dr Lisa Chimes.

Prevention is the sweetest solution

There are a few ways owners can make it harder for pets to pilfer their alcohol. Firstly, they should be careful with alcohol containers and glasses, always disposing of remaining drinks and keeping bottles tightly shut.

Read more:The curious character of cats – and whether they are really more aloof

Watch out for home brewing kits, which pets may access. Food items containing alcohol should also be kept out of reach, so keep an eye on that brandy-rich Christmas pudding. Pet parents should be especially careful during social festivities, as opportunity abounds to dip paws into cocktails, wines, beers and other unattended spirits.

Ultimately, if your pet does have an unsolicited drink, take them to the vet immediately. Enjoy the silly season, but remember to look after your furry friends by keeping your Christmas cheer (or your Christmas booze, at least) to yourself.

Wendy Brown receives funding from both internal and external sources to conduct scientific research in her role as a Senior Lecturer in Animal Science at the University of New England.

Joanne Righetti does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Authors: Wendy Brown, Senior Lecturer, University of New England