My child has glue ear – what do I do?

- Written by Chris Brennan-Jones, Senior Research Fellow, Telethon Kids Institute, University of Western Australia

Repeated ear infections and prolonged episodes of glue ear can result in permanent hearing loss.from shutterstock.com

Repeated ear infections and prolonged episodes of glue ear can result in permanent hearing loss.from shutterstock.comAround one in four Australian children will have recurrent ear infections in their first three years of life. This decreases as children get older. But by the time children start school, one in ten will still have glue ear, which could have a significant impact on their early learning.

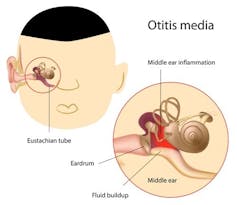

Glue ear is a form of ear infection also known as otitis media with effusion. It occurs when the middle part of the ear (behind the ear drum) fills with a sticky, glue-like fluid instead of air. This fluid dampens the vibrations made by sound as it travels through the eardrum and to the cochlea – the spiral-shaped part of the ear where the vibrations are converted to signals sent to our brain, allowing us to hear.

For children with glue ear it is like someone has turned down the volume of the world. This is why these children may appear to have selective hearing. Repeated ear infections and prolonged episodes of glue ear can result in permanent hearing loss. The impacts on a child’s development stretch well into adulthood.

So what should you do if your child has glue ear? And how can you prevent them getting it in the first place?

One theory is that glue ear persists after having a cold if the Eustachian tubes are unable to clear the mucus.from shutterstock.com

One theory is that glue ear persists after having a cold if the Eustachian tubes are unable to clear the mucus.from shutterstock.comWhy do kids get it?

Otitis media can run in families and we know there is some genetic susceptibility to this disease. However, research has also shown cases of glue ear in Australian children peak during winter months, related to the increase in colds, and at the start of the school year, when children may be exposed to new bugs from other kids.

The exact cause is poorly understood, but bacteria and viruses associated with coughs and colds are often the initial cause of ear infections.

Read more: What is the common cold and how do we get it?

One theory is that glue ear persists after a cold has cleared due to a dysfunctional Eustachian tube, which links the back of the throat to the middle ear. When mucus eventually clears from the nose and throat after a cold, the theory proposes that instead of draining from the ear through the Eustachian tube as it should, it gets stuck in the middle ear, resulting in glue ear.

Bacteria also develop something called biofilms (slime) as a protection. This can make the bacteria up to 1,000 times more resistant to antibiotics, meaning they can’t be effectively treated. These bacteria are also able to hijack a child’s immune response, making immune cells spit out a sticky net of DNA that, instead of killing the bacteria, creates the sticky glue that provides the bacteria with a home.

Together these increase the ability of glue ear to persist or re-occur. This results in longer periods of hearing loss and leaves children at a greater risk of developmental problems.

How can it be treated and prevented?

There is no silver bullet that will prevent glue ear. But you can do to some things to reduce the risk of persistent glue ear.

These include reducing exposure to cigarette smoke and making sure your child has had all their vaccinations. Encouraging children to wash their hands and other healthy hygiene habits, like blowing their noses, are also important. Research has also shown breastfeeding your child has some protective benefits from otitis media.

It’s important to encourage your child to wash their hands and blow their nose.from shutterstock.com

It’s important to encourage your child to wash their hands and blow their nose.from shutterstock.comVaccines (in particular, pneumococcal conjugate vaccines) can help reduce ear infections and subsequent glue ear. But current vaccines can cover only a small proportion of the possible bugs that cause ear infections. New vaccines are being developed against this bug and also a bug called nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae, which is now the main cause of ear infections in children.

Once glue ear is identified, there will usually be a “watch and wait” period of around three months. This is particularly important if glue ear is identified during one of the peak periods when it may resolve by itself without intervention. Antibiotics may offer very limited benefit and will not be recommended in many cases.

Read more: Should kids be given antibiotics in their first year?

For children who have persistent glue ear, a small operation commonly known as grommet insertion is performed. Grommets are devices that ventilate the middle ear and prevent fluid accumulating. These surgeries are one of the most common surgical procedures, with over 30,000 performed every year in Australia.

Grommets are usually an effective treatment for glue ear and improve hearing almost immediately. However, like any surgery, there are risks and potential complications.

New drug therapies are also being developed, including one that dissolves the glue in glue ear. This may reduce the need for repeat grommet surgeries in cases of persistent glue ear.

Why is it such a problem?

One of the key challenges in treating glue ear is to identify it in the first place. It can be hard for parents to spot the signs, which can include hearing difficulties (such as your child asking you to repeat words) and occasional pain and pressure. Undiagnosed and untreated glue ear can have serious developmental consequences for children.

A recent parliamentary inquiry into hearing health has suggested all children be screened for hearing loss during their first year of school. This could be hugely beneficial in identifying children with glue ear who have no other obvious signs.

Aboriginal children experience more ear infections, longer periods of glue ear, and more severe hearing losses than other children. In fact, Aboriginal children in Australia have the highest rates of otitis media in the world.

Read more: Aboriginal kids have the highest otitis media rates in the world

Initiatives to provide early identification and treatment for ear infections and glue ear, such as the Nyoongar Djarli Waakinj ear health program at the Telethon Kids Institute in Perth, the WA Child Ear Health Strategy and other programs like Deadly Ears, are helping to reduce the developmental impact of otitis media and close the gap for ear health in Aboriginal children.

Chris Brennan-Jones receives funding from the NHMRC CRE for Ear and Hearing Health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People (CRE_ICHEAR).

Ruth Thornton receives funding from the BrightSpark Research Foundation in the form of a research fellowship, as well as from the NHMRC, the Western Australian Health Department and the Princess Margaret Hospital Foundation in the form of research grants .

Authors: Chris Brennan-Jones, Senior Research Fellow, Telethon Kids Institute, University of Western Australia

Read more http://theconversation.com/my-child-has-glue-ear-what-do-i-do-83815