What prospective parents need to know about gene tests such as 'prepair'

- Written by Gina Ravenscroft, Research Fellow in neuromuscular disease and genetics, University of Western Australia

Couples who are carriers of genes for recessive diseases don't show any symptoms.Photo by Drew Hays on Unsplash, CC BY

Couples who are carriers of genes for recessive diseases don't show any symptoms.Photo by Drew Hays on Unsplash, CC BYResearchers recently renewed calls for all prospective parents to be offered testing for gene mutations that could be transferred to their child. This came after a study published in the journal Genetics in Medicine found 88% of couples weren’t aware they were carrying mutations for three serious diseases: cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy and fragile X syndrome.

Diseases like cystic fibrosis have significant health consequences.from shutterstock.com

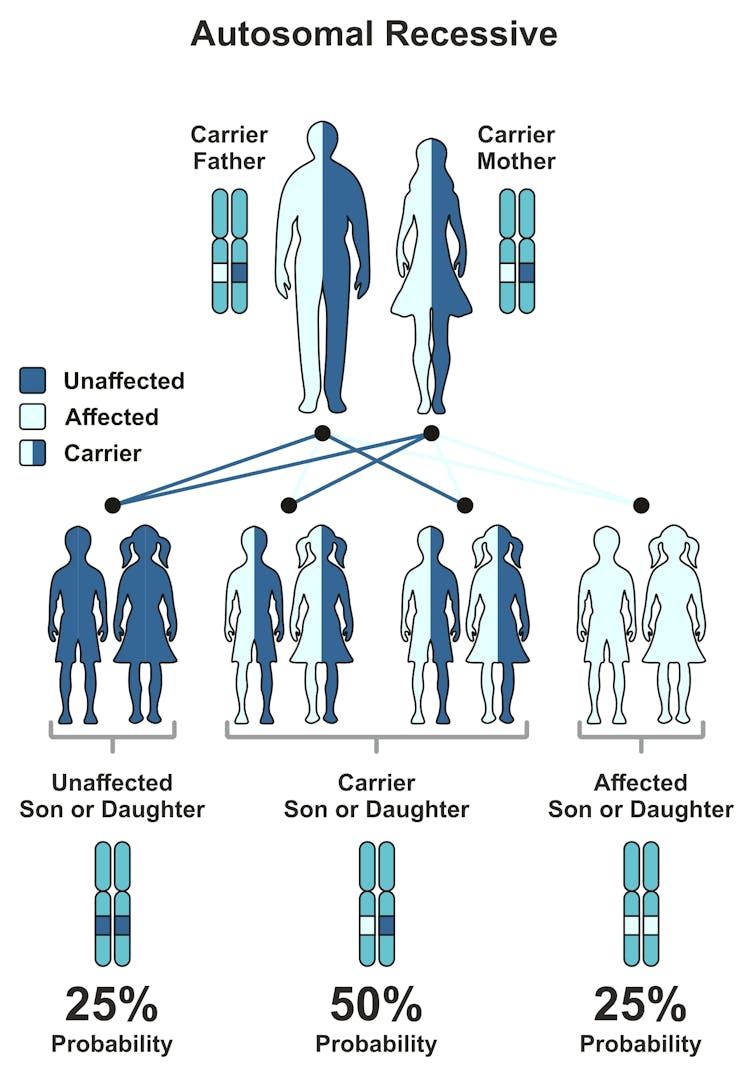

Diseases like cystic fibrosis have significant health consequences.from shutterstock.comThese three diseases have significant health consequences and are among the most common recessive diseases. This is where only one parent carries a copy of the gene mutation (both parents need a copy for the child to become sick) and shows no symptoms. A healthy individual who carries a single recessive mutation is called a carrier.

Recessive diseases cause many severe disorders in children, but most of us who are healthy carriers don’t know how many or what mutations we carry. Pre-pregnancy or preconception carrier screening allows healthy couples to identify mutations they carry before they become pregnant.

So, what is the test used in the recent study, and should it be available to all prospective parents?

What genetic tests are available?

The recent study used the “prepair™ test” to screen couples. It was conducted by the Victorian Clinical Genetics Service (VCGS), which provides the test to the public. The number of pregnancies affected with one of these three diseases (cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy and fragile X syndrome) during the course of the study was one in every 1,006 women. This figure is comparable to that of live births affected by Down syndrome.

Currently, government subsidies for genetic testing and counselling are only available for couples once they have had a child with a suspected inherited disease or if there is a history for a particular disease in the extended family.

Read more: Why should we offer screening for Down syndrome anyway?

Aside from the VCGS, there are at least five other providers in most Australian eastern states offering tests for different sets of recessive disorders. All five are consumer-pays tests. They range from A$350 to A$750, depending on the number of genes tested.

The largest gene panel tests for 590 diseases and costs the most, while others only test for the same three recessive diseases VCGS offers. Another test screening for 175 recessive conditions is provided by Counsyl through Australian clinicians.

What can I expect from the prepair™ test?

The VCGS prepair™ screens for specific mutations in the three genes causing the three diseases. Couples or individuals are considered at “increased risk” if they both carry a mutation for the same one of the three screened diseases.

The VCGS prepair™ genetic test is usually first offered to women before, or early, in their pregnancy (less than 12 weeks) by health professionals. These are usually GPs and obstetricians, as they are generally the first point of medical contact for soon-to-be-parents. Partners of carrier women are then offered testing.

If each member of the couple carry the gene mutation for the same disease, their child has a 25% chance of the disorder.from shutterstock.com

If each member of the couple carry the gene mutation for the same disease, their child has a 25% chance of the disorder.from shutterstock.comAll carriers are offered a genetic counselling appointment and an appointment with a paediatric sub-specialist who has expertise in the specific disease. Results are also discussed with the referring health professional. For individuals or couples not identified as carriers, the report is sent to the referring health professional and no further testing or follow-up is required.

If couples are carriers for mutations in the same gene, any of their children have a 25% chance of being affected by the disease. If couples do not carry any of the mutations the VCGS test screens for, they are considered at “low risk” of having an affected child.

But while the risk of having a child affected by a genetic mutation is greatly reduced, it is not eliminated. The main benefit of tests screening for hundreds of genes is that a couple can know their carrier status for many more recessive diseases.

How can couples use the test to make decisions?

Understanding what it means to be a carrier and a high-risk couple allows prospective parents to decide how they want to approach conception and pregnancy. At-risk couples and those with a previous history of recessive disease frequently want to avoid having an affected child. Couples may then opt for in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) to select only healthy embryos (without two mutations) for implantation.

Read more: Rest assured, IVF babies grow into healthy adults

Couples may also decide to fall pregnant naturally and then test the fetus, through a test called chorionic villus sampling, towards the end of the first trimester to determine whether the baby carries two mutations. Or they may decide to adopt or forego having children.

TedXTalks.If a couple decide to continue a pregnancy, knowing ahead of time their baby will be affected allows them time to process and make lifestyle plans to accommodate for their changing circumstances and engage with support groups. Rare disease groups such as Spinal Muscular Atrophy Australia provide support in care options, resources and choices for families living with spinal muscular atrophy. If therapies are available, it also allows for treatment of the disease from birth.

As no screening test guarantees a healthy baby, genetic counselling is crucial to explain the limitations and risks to couples. Counselling involves communicating complex genetic information clearly to couples, clarifying any doubts and misconceptions and more importantly to interpret and explain test results.

Should all couples have this test?

Our experience shows access to this kind of genetic testing can be challenging. Generally this is because health care professionals can be unaware such tests are available locally; or be unfamiliar with how blood should be collected, or where to send specimens for testing.

Preconception carrier screening tests have also been confused with other prenatal tests, particularly the non-invasive prenatal test (NIPT), by both parents and health care professionals. In this situation, parents may feel reassured their child does not have a genetic disease, but NIPT only tests for chromosomal problems (like Down Syndrome or trisomy 21) not single gene disorders.

This clearly shows awareness and education is critical among health care workers for preconception carrier screening programs to be successful.

Read more: What is pre-pregnancy carrier screening and should potential parents consider it?

Given the risk for an affected child for the three common recessive diseases is similar to Down syndrome, it may be considered carrier screening should be made available to everyone in Australia. But there are a number of issues that need to be addressed for this to happen.

These include consideration of the number of severe childhood disorders to be included for screening and who the target population would be. Studies are also required to inform the government of the most cost-effective method of offering such a test.

If a carrier screening program is to be implemented by the government, the infrastructure and clinical resources required to appropriately administer and sustain such testing must be explored to ensure all couples are informed and counselled as required. And subsidy of pre-implantation genetic diagnosis should also be considered for all carrier couples.

Pilot studies in different states may help explore how best a carrier screening program can fit into the different health systems in Australia.

Gina Ravenscroft receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council and the French Muscular Dystrophy Association (AFM).

Michelle Farrar receives funding from Motor Neuron Diseases Research Institute of Australia

Nigel Laing receives funding from The Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Association Francaise contre les Myopathies (AFM), the US Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA), a Foundation Building Strength for Nemaline Myopathy (AFBS).

Royston Ong receives scholarship funding from the Australian Postgraduate Award and the Australian Genomic Health Alliance.

Authors: Gina Ravenscroft, Research Fellow in neuromuscular disease and genetics, University of Western Australia